Assaultive Behavior and Workplace Violence - 2 Contact Hours

Course Outline

- Outcomes

- Objectives

- Introduction

- Definitions

- Understanding Assaultive Behaviors: Including Peer-to-Peer Incivility

- Violence Risk Assessment Tools

- Case Study 1

- Mitigating Agitation (De-escalation)

- Case Study 2

- Coping Strategies and Emotional Safety

- Harm Reduction by Administration and HCWs

- Case Study 3

- Fostering Clinical Judgement in Violent Situations

- Case Study 4 (actual Type 4 violent event)

- Conclusion

- References

Outcomes

≥ 92% of participants will know the extent and types of workplace violence in healthcare with methods of preventing and mitigating future events.

Objectives

Following completion of the course, the participant will be able to:

Classify assaultive behaviors, including peer-to-peer incivility.

Assess assault risk assessment tools.

Illustrate how to mitigate agitation.

Explain coping strategies and emotional safety.

Relate harm reduction strategies in the workplace.

Outline ways to utilize clinical judgment in violent situations.

*This material does not cover physical or chemical restraint guidelines.

Introduction

Assaultive behaviors in the healthcare workplace are multidimensional subjects requiring complex reasoning and a comprehensive approach to understanding. Management (administration) and healthcare workers must act together to make the workplace safer and reporting easier. In 2022, Congress passed the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act due to increasing violent episodes towards healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. This bill requires the Department of Labor to address workplace violence (WV) in health care, social services, and other sectors. Specifically, the Department of Labor must issue an interim occupational safety and health standard requiring certain employers to protect workers and other personnel from WV. The standard applies to employers in the healthcare sector, social service sector, and sectors that conduct activities similar to those in the healthcare and social service sectors (Congress.gov, 2021, sec. 101 part a.).

Verbal, such as cursing Physical (like biting, pinching, slapping, kicking) Electronic (cyberbullying) Psychological threats of brutality (intimidation, threatening, bullying)

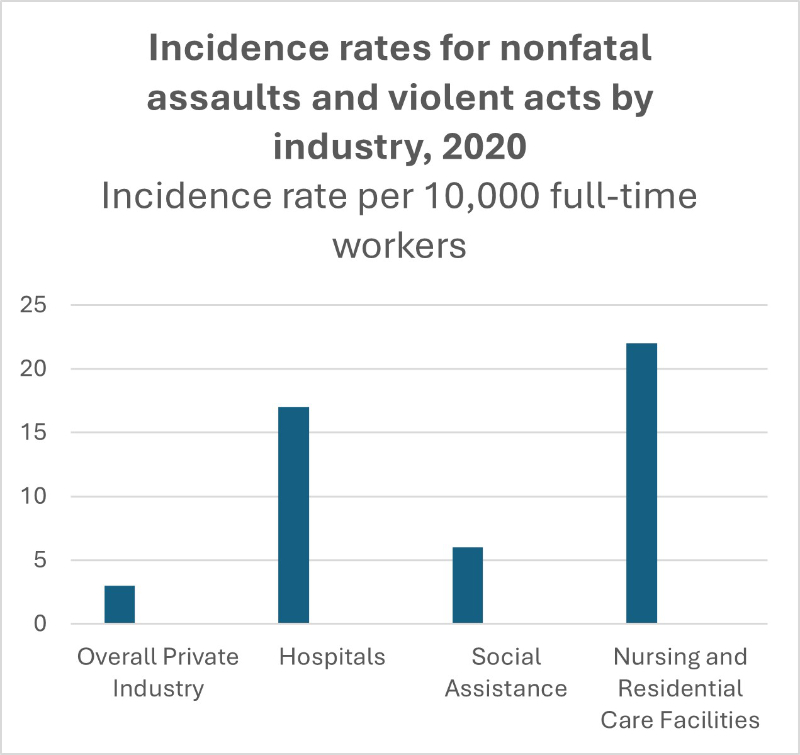

By far, the most common type of workplace attack against healthcare workers (HCWs) is from patients and family members and is usually verbal. Second is physical violence from that same group, and finally, there is psychological aggression from any person in the workplace (WP). Healthcare workers are more than four times as likely to be hurt at work from hostility than the nonmedical public is in their workplaces (BLS, 2020). Patients are at risk for collateral damage as well. Some researchers have placed WP suicides on the list of WV. Braun et al. (2021) report that between 2003 and 2016, there were 61 fatalities among HCWs. The study also showed that most were suicides (32), and the rest were homicides (21) or of unknown intent (8). The suicides occurred more in the clinics, and homicides occurred more in hospitals. While rare, fatalities in the WP can have a devastating effect on others who may be present. Therefore, prevention and recovery training should include suicide as well as homicide (Braun et al., 2021). There is more to WV than the possible acute physical damage sustained. Studies repeatedly show that incremental psychological damage is done as well, resulting in time loss at work from burnout, anxiety, depression, and job and occupational changes (De Sio et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2023). Workplace violence worldwide in healthcare facilities is a quarter or more of all occupation sectors. Lim et al. (2022) highlight that large groups of family and friends in crises, such as a severe injury to a family member, are where this offense is more common. This is mainly seen in the emergency, ICU, and psychiatric units. However, WV occurs in every area of healthcare. An interesting study showed that the typical consumer (without mental or drug issues) has just as much of a chance of being a perpetrator of workplace injury. Aljohani et al. (2021) analyzed WV studies in emergency departments without mental health or drug abuse perpetrators. They also did not include any prehospital transportation by paramedics.

Figure 1: Incidence Rates for Nonfatal Assaults and Violent Acts by Industry (BLS, 2020)

Definitions

- Debriefing- A “structured, intentional yet informal, quick information exchange session designed to improve team performance and effectiveness through lessons learned and reinforcement of positive behaviors (AHRQ, 2024).”

- Bullying- Also known as lateral or horizontal violence or co-worker incivility. The American Nurses Association defines nurse bullying as “repeated, unwanted harmful actions intended to humiliate, offend and cause distress in the recipient (ANA, n.d.).”

- Cyberbullying- Intimidates or humiliates (someone) persistently using the internet, text messaging, or another form of electronic communication (Farlex, n.d.).

- Verbal Judo©- A non-violent communication method designed for law enforcement by Dr. George Thompson, based on the principles now used for HCWs (Thompson & Jenkins, 2013).

- Workplace violence- The Joint Commission defines workplace violence as an act or threat occurring at the workplace that can include any of the following: verbal, nonverbal, written, or physical aggression; threatening, intimidating, harassing, or humiliating words or actions; bullying; sabotage; sexual harassment; physical assaults; or other behaviors of concern involving staff, licensed practitioners, patients, or visitors (TJC, n.d.b).

Understanding Assaultive Behaviors: Including Peer-to-Peer Incivility

Balance Scales

What prompts people to become agitated and assaultive? There is an imbalance of power inherent in healthcare. Violence of any kind may occur because of this power imbalance. The patients, their families, and friends (consumers) are on the lower end of the power balance, creating feelings of helplessness and fear.

Hypersensitivity to perceived threats Overreaction to a lack of safety cues - Persistent and pervasive worries about future threats

Negative coping skills - Dysfunctional cognitive abilities

Many authors have written about workplace violence prevention (WVP), and it is generally known that there are four types of assaultive behaviors in the workplace.

- Interpersonal assaultive behavior is when someone other than staff is physically assaulting a staff member. Usually, a patient, family, or visitor.

- Horizontal assaultive behavior is when physically assaultive behavior is from one staff member to another, such as rape or other battery.

- Verbal assaultive behavior is verbal abuse against anyone, by staff or non-staff members, such as using foul language, yelling, and threats.

- Psychological assaultive behavior can be against anyone, by staff or non-staff members, such as intimidation, shaming, coercive power use, incivility, and bullying.

NIOSH (2020) has four more specific workplace violence levels.

- Type 1 Criminal: This is when someone has no reason to be in the business unless committing a crime there.

- Type 2 Customer-to-provider: This is when the patient commits an act of violence on the HCW.

- Type 3 Worker-to-worker: This includes any bullying, threats, actual physical violence, rape, or sexual assault between co-workers.

- Type 4 Personal relationships: This includes domestic violence that spills over into the workplace.

In any workplace suffering, the final "trickle-down" victims are always the patients, as it has been conclusively shown that WV towards the HCWs can lead to depression, anxiety, lower morale, missed shifts, job changes, and poorer quality patient care in general (Edmonson and Zelonka, 2019).

Violence Risk Assessment Tools

Brøset Violence Checklist (BVC)

Brøset Violence Checklist (BVC): BVC is a prediction tool that assesses a patients current confusion, irritability, boisterousness, verbal threats, physical threats, and attacks on objects as either "present" (1 point) or "absent" (0 points). The maximum number of points is six; anything greater than two requires preventive measures and a plan for a possible violent event. This tools result may be used as a vital sign (Hvidhjelm et al., 2023) or as an item in a shift change report (Lockertsen et al., 2021).

STAMP

STAMP (Luck et al., 2007)

- S- Staring and eye contact

- T- Tone and volume of voice

- A- Anxiety

- M- Mumbling

- P-Pacing

ABC

ABC (DOES THE PERSON.....)

- A- Aggression History (have a known assaultive history?)

- B- Behavioral Concerns (show signs of anger, clenched fists, demanding, resisting care, threatening, raised voice?)

- C- Clinical presentation (appear intoxicated by alcohol or drugs, acting erratic or irrational?)

Adapted from the Queensland Occupational Violence Patient Risk Assessment Tool (Caliban et al. 2022), if the answers are yes to two or more of these, then there is a high chance of assaultive behavior.

Risk assessment tools are often used in emergency rooms due to the volatile nature of some injuries and, historically, are most at risk for WV along with ICUs and psychiatric departments. No tool is perfect, and sometimes "gut feelings", alert observation, and situational awareness are an additional help.

Crossed arms, pushed out chest, clenched jaw or fists, pointing, bowing up Abnormal expression for the situation, becoming red in the face Stepping into your or someone elses personal space - Breathing loudly, big sighs, fast breathing

- Throwing hands up into the air expressively, using larger-than-life movements of limbs

- Shutting down and ignoring your words. Suddenly, leaving in the middle of a rant

Using "You" phrases, "You are going to be sued", and "You people are idiots" Using foul language Raised or loud voice Growling, muttering, talking to themselves under their breath Asking irrational or bizarre questions. "Do you want my mother to die?" "What is this place doing?"

Part of prevention is anticipating and recognizing when this apparent anger is going to turn from anxiety to actions that may ultimately hurt or kill someone. That is best achieved through regular comprehensive training for all healthcare providers, including pharmacists and healthcare students (Jeong and Lee, 2020).

In the case of peer-to-peer bullying and verbal assaults, these are usually due to poor communication skills, jealousy, racism, ageism, and feelings of superiority or inferiority of the perpetrator (Edmonson and Zelonka, 2019). In the case of cyberbullying, the damage to the victim may be much worse than face-to-face bullying. The results are anonymous, cant be walked away from, and may be shared worldwide. According to Ikeda et al. (2022); La Regina et al. (2021), and Oguz et al. (2023), the possible types of cyberbullying are emails, texts, photos, rumors, deep-faked information, stalking, identity theft, and more. This exposes the target repeatedly on social media, emails, and texts, destroying the feeling of privacy and security and leading to the same or more severe reactions physiologically and psychologically (La Regina et al., 2021). A combination of face-to-face bullying and cyberbullying is much more devastating to the target (Ikeda et al., 2022). Again, training in coping skills and communication skills, such as non-violent communication, Verbal Judo, and therapeutic communication, can mitigate peer-to-peer assaultive behaviors in the workplace. Reporting WV is necessary; bullying and other peer-to-peer insults and harassment should not be treated as expected or part of an "initiation" to a job (ILO, 2024). No one is excluded from reporting, bystanders included. As per Oguz et al. (2023), who regard cyberbullying as a crime, the employee (target) should be protected from the cyberbully (perpetrator) by administrators, supervisors, and managers (guardians) through electronic device controls, policy making, and vigilance.

Case Study 1

Melanie had been working at a healthcare facility for six months when she overheard one nurse tease another nurse who had just started employment there. She noticed that the nurse told the new nurse that she “Wouldn’t last long, thank goodness” because the new nurse had commented that she was tired. Later, Melanie heard the same nurse reporting to the supervisor that she thought the new nurse “Might be thinking of quitting already.” She remembered that this same nurse had acted that way towards her when she first started and still did sometimes. At first, Melanie had developed an “I don’t want to go to work” attitude due to it. Her facility had an Employee Assistance Program (EAP), which she called to find out what to do. The program counselor invited her to journal her feelings and try to find one good or helpful thing every day. The counselor made several suggestions to increase her resiliency, such as meditation, self-affirmation, and positive coping ideas. She encouraged her to call back regularly until she felt she had a good outcome. Melanie talked to the counselor several times and implemented many of her suggestions. She journaled her feelings and decided she could ignore the poor behavior of the other nurse since the bills had to be paid, and she felt lucky to have a good job. However, she felt she could not report the bullying for several reasons. Early on, she heard the supervisor say, “You girls work it out; you are adults.” Melanie had looked at the policy for poor behaviors on the job and learned that the supervisor was not following the policy. Then, she felt she could do nothing about this co-worker's incivility without getting her supervisor in trouble. She did not want to be pointed out as a troublemaker. Besides, who would the administration believe if it came down to it? She felt that maybe the other nurse had to learn like she did. Despite Melanie’s friendly attention and occasional advice to her, the new nurse quit after just a few weeks.

Points to consider:

- Were Melanie’s feelings and inaction reasonable?

- What made Melanie able to endure the incivility?

- What would you have done?

- Was the supervisor’s response to the bullying avoidance and distancing herself from accountability?

If you agree with the supervisor in this case, you should know that the avoidance method of curbing bullying among HCWs is not successful since over 50% of HCWs report at least one case of bullying in the last week!

You might be a bully if…

According to psychologist Chantal Gautier (2019), you might be a bully:

If you make people angry or cry often, or you can’t understand why you have upset someone. Sometimes, you shout or complain about one person's errors in front of others, including consumers. Suppose you seem to thrive around insecure people and feel good when pointing out others' errors. You enjoy telling others about real or made-up things about someone. You deliberately ignore others and leave them out of events or omit information vital to their job performance. You might be a bully if you use your occupational power to remove or add responsibilities to someone without an excuse or explanation. One important sign of bullies is that they do not have empathy for others. They do not understand and can’t imagine their intentional behavior may have a genuine and lasting negative effect on the person they bully. But then, if they have no empathy, they may not care. Take the empathy test in the resources section at the end of the course.

Mitigating Agitation (De-escalation)

Much of the literature is about de-escalating a situation when someone becomes agitated.

Have compassion for the person acting out. They believe what they are upset about. They are anxious and are not cognitively processing well. - Allow enough personal space. Provide space for either party to exit safely. Feeling threatened or angry, people feel safer if not approached too closely. Keep the exit clear. Don’t allow yourself to be trapped by a desk, for instance.

Be calm and do not allow yourself to take anything said or done personally. Emotional reactions are likely to increase violent behaviors. Keep an open stance. - Listen to the complaint with great attention. Attempts to understand what the person needs are calming. Rephrase what the person has said for clarity. Try empathizing when you think you have the issue nailed down, such as “I see that worried (scared, troubled) you” or “That would make anyone feel that way.” Don’t interrupt, as this is seen as discounting their feelings.

- Apologize for what you can honestly be apologetic for. “I’m sorry you feel so uncomfortable.”

- Try to keep to the point if the person wanders verbally. “What can I do to help you with this right now?”

Keep it simple. Don’t use medical jargon or “You” phrases (“You need to…, You should…”). Provide choices; people with little to no weight in the healthcare power balance need to feel they have control over something. This is especially true for patients. Use therapeutic communication when you can. - Allow silence. Let silent breaks in the conversation be. It decreases stress, does not feel rushed, and gives the perpetrator time to think about your words.

- Report what happened. Proper reporting is how administrators can track whether training is working as it is, if it needs to be repeated, or if an enhanced program is called for.

Case Study 2

Mrs. Lura Rahim is a 90-year-old patient who experienced a fall at home three days ago and has been bed-bound since then. She broke her hip, which cannot be repaired due to her disease burden, overall physicality, and age. She is entirely incontinent of bowel and bladder and has pain in her hip during any movement. She refuses food and medications. She refuses to answer questions and turns her head away whenever anyone tries to talk to her. She will say “No” and loudly scream about being turned or cared for in any way that requires movement. She is assaultive to staff (pinching, slapping, throwing food and other items), and everyone has been warned to “Watch out” in her room. Some of the staff think she is angry that her son has put her in rehabilitation and that she wants to die. On the third day, the supervisor called the son, Najir, to discuss his mother and her needs. He reports that since she came from their home country, she has not adapted well; she doesn’t like the food, and she doesn’t speak English. He further states that she had servants in their country and her own home. He brought her here because his father passed away just a month ago, and her health was poor. He is the only living child. He hadn’t hired servants for her here yet because he could not find any that spoke the language and that was acceptable to both him and his mother. He reports that this town does not have a large community of Middle Eastern people. But simultaneously, he remains optimistic that she will be fine when she adjusts to it here. He is encouraged to visit often, bring traditional, native, home-cooked meals to supplement what she tells him she will eat, and help her understand that her pain and other illnesses can be treated with medications. He is also urged to ask her to treat the HCWs respectfully without attempting to hurt them.

Points to consider:

- Was prioritizing patient needs optimal?

- Were the patient’s reactions understandable?

- What could have been done differently?

- What was the family responsible for?

When patients are the perpetrators, there are several points to remember:

- Don’t surprise patients. A bad start to a patient encounter sets the tone for the entire meeting.

- Ask permission to touch patients.

- Let them know what you will do at every step and what they can do to help.

- Be on the same level for conversation (though out of arm’s reach). If they are lying down, sit down to speak with them; if they are standing, stand up.

- Keep your voice calm even if they don’t comply with directions.

- Ask what you can do to help them today. Do the best you can to make it happen. Keep them informed of the results of your efforts.

- Show compassion and empathy. Listen to them. Sometimes that’s all they want.

- Take someone with you, as this may forestall or help you in case of a problem.

- Do not share your workload or frustrations with them. It’s not about us, it’s about them.

- Smile, use a relaxed stance, keep your arms loose at your sides, and only touch when assured they are open to a pat on the arm or hand holding.

Coping Strategies and Emotional Safety

“The defining characteristics of a highly reliable organization include healthy work environments, emotional and physical safety, and a culture that is “just,” where it is safe and expected to speak up” (Edmonson and Zelonka, 2019).

A list of ways to become more resilient was collected by Katella (2022) from COVID-19 town halls, discussing how to overcome psychological stressors. People who were doing well helped others, and evidence-based methods were encouraged by the organizers. Those more likely to have positive outcomes used these eight ideas often:

Acknowledge and accept what you can’t do and figure out what you CAN do.

Learn to see things from a more positive point of view, such as practicing gratitude for what you DO have.

Build your social connections; go beyond “hi and goodbyes.” Develop deeper connections in your close social circle.

Do something for yourself that makes you feel fulfilled.

Do things that uplift your spirits on purpose. Go walking outside, paint a picture, sew a toy, or do whatever you enjoy.

What can you do to make your job a better place for you to be?

Make family and friends’ emotional health a priority.

Avoid dwelling on the negative, such as not watching the news channel for hours, and avoid the strictly pessimistic people who want to expound on it.

They also mentioned that when you can’t make any of this information work for you, you should “Get help” (Katella, 2022). Sometimes, a friend or a family member can help, but a counselor, preacher, psychologist, or other non-invested professional can feel better. There are also artificial intelligence-guided cognitive behavioral therapy programs that can be accessed via apps on a smartphone or computer.

Harm Reduction by Administration and HCWs

Another situation that may cause hostility in the healthcare facility is when HCWs are judgmental towards patients. Febres-Cordova et al. (2023) report that abuse from HCWs toward substance-using, abusing, or addicted patients is also a workplace aggression issue. The report states that this abuse of power is verbal and physical in that these patients are often considered to be “drug-seeking” and, as such, are not always treated for pain or anxiety. These patients are often verbally abused, and their accounts of pain are discounted. Their behaviors to attempt not to have uncontrolled withdrawal events by asking for medications such as CNS depressants (diphenhydramine or others) as often as they can have them (often by the clock) is seen negatively by HCWs.

Providing care based on respect for the person rather than judging and Not attempting to punish the user verbally or physically Not bullying, withholding care, or coercion

Racism, ageism, and other characteristics that may differ due to cultural influences or socioeconomic levels cannot interfere with care.

Case Study 3

Mr. Jacks is a 43-year-old man who had a motorcycle accident while riding with his club. He is a large man weighing 280 pounds and standing 5’11”, dressed in a t-shirt and jeans cut off at the knee on his left leg, with a leather jacket covered in club patches. The emergency department staff considered his appearance dirty, scruffy, and scary. His “brothers” in the club are also large, long-haired, bearded and dressed in leather. They explained that a deer ran out of the roadside brush and hit him broadside. His leg was lacerated open through the entire calf. Due to the trauma of the event and the size of the laceration, his skin could not be closed over his calf muscles and associated structures. The physicians used an area of skin on his opposite hip and lower back to harvest skin for an allograft. However, daily care of the two operative sites was very painful. His club always left a member in his room to be his advocate. When one of his club brothers complained that his treatment should be preceded with pain medications, he was told by the charge nurse that the hospital was not interested in feeding Mr. Jack’s drug habit. There was a record of an overdose in the past. The brother reported to the hospital administrator that if his brother wasn’t sufficiently treated for pain before daily treatments, he’d purchase something on the streets to help him. The administrator saw the earnest caring of the “brother” and visited the patient, spoke with the physician, and discovered that there was a PRN order for opioids to decrease the severe pain already written and had been ignored due to the stigma of this patient’s medical history and motorcycle club affiliation. Points to consider:

- Was kindness or caring employed by the nurses in this case?

- If the person had been clean-cut and without a substance abuse history, would this have happened?

- What if this man had no “brothers” or anyone else to advocate for his needs?

- Does this raise the level of WPV towards this patient?

While WPV is devastating for the people trying to help patients, it is callous cruelty for those HCWs to injure a patient deliberately. It is never acceptable to harm a patient deliberately and without provocation. Our “Duty to Care and Do No Harm” is actionable by our professional boards and civil and criminal laws.

How can we, as healthcare professionals, reduce the amount of harm caused by assaultive behaviors from patients, patient’s family members, visitors, and other staff? There is a lot of agreement on that. Specific measures from patients, family members, or other staff will be helpful, whether the aggression is verbal, physical, or psychological. To decrease the lasting psychological harm that, if ignored, can lead to depression, leaving the job or even the profession, consider these interventions.

- Treating each other with kindness and respect.

- Believing the reporter, not holding the reporter responsible for mistreatment.

- Debriefing the victims and bystanders where possible.

- Mandatory counseling for the victim or victims.

- Paid time off to get care without recrimination.

- Training should include meditation, mindfulness teaching, and positive coping skills.

- Administration must actively seek and address feedback (Strid et al., 2021).

- Environmental changes include large, comfortable waiting areas without blind spots.

- Increasing staffing to avoid long wait times.

- Increasing security staff in public entry points and on floors with higher instances of WV.

In the case of peer-to-peer incivility, peer group support during the event (standing up for what is right) and afterward is needed. Having a well-defined policy and transparent follow-through from a perpetrator's direct supervisor will also help (Edmonson and Zelonka, 2019).

Fostering Clinical Judgement in Violent Situations

Training (personal and organizational) cannot be expressed enough as a tool that is easy to implement. Educators and counselors are usually already present in most organizations. WVP training should encompass all areas, such as:

What to look for, and what policy allows you to do about it? If you must defend yourself, stop the force only through your actions. Anticipation and avoidance may be the easiest and best answer (ANA, n.d.).

Although rare, be alert for hiding places if the situation devolves into a live shooter situation. Know when to shelter in place, bar the door, and call 911 in a live shooter situation. In this situation, if you must defend yourself, stopping the force may mean producing similar or greater power with whatever weapon you have (Texas State University Police Department, n.d.).

- How to recover from an event such as assaultive behavior without having lasting emotional issues, such as PTSD.

- Learning and using positive coping skills to become a more resilient person. Knowledge is power.

- Further training such as this course will help you learn more about what to do in these situations.

You can join a live shooter simulation event to learn how to:

→ Avoid the shooter,

→ Deny access to yourself, and

→ Defend yourself if required (Texas State University Police Department, n.d.).

Case Study 4 (actual Type 4 violent event)

Not all assaultive behavior stems from reality. There are situations where unprepared healthcare workers are simply surprised, such as the incident in Dallas, TX, in October 2022. A man was visiting his girlfriend who had just had their baby. No one knew, except his parole officer and his girlfriend, that this visitor was on parole after a violent aggravated robbery conviction and released with orders from the court to wear an ankle monitor. No one except her and his parole officer knew at the time that he had a history of violent criminality and had previously removed his ankle monitor four times. He had permission from his parole officer to visit his new baby at the maternity ward. He was intoxicated on arrival and irrationally became jealous, thinking a man was hiding somewhere in the room. He pulled out a gun and beat his girlfriend on the face and head several times while she held the baby. He shot and killed a nurse and a social worker who came in or near the room to care for the mother and baby. The mother recovered, and the baby was not harmed. The security officer arrived as the perpetrator was holding the mother hostage and shot the man in the leg (Osibamowo, 2023). It is unclear whether the hospital knew the man’s record and, if so, what steps they took to address the risk.

Points to Consider:

- What could the hospital have done if they had known his status?

- If you had known of the father’s record, what steps might you have taken to address the risk?

- What will the long-term psychological problems be for the rest of the staff (Jones et al.,2023)?

- Could any of this be prevented?

The International Labor Organization authored a world treaty that each member country would:

- Ensure that relevant policies address violence and harassment;

- Adopt a comprehensive strategy to prevent and combat violence and harassment;

- Establish or strengthen enforcement and monitoring;

- Ensure access to remedies and support for victims;

- Provide for sanctions;

- develop tools, guidance, education, and training and raise awareness in accessible formats as appropriate; and

- Ensure effective means of inspection and investigation of cases of violence and harassment through labor inspectors and other competent bodies (ILO, 2024, p.24).

To date, all but seven member states of the United Nations are members of the International Labor Organization (ILO, 2024).

Conclusion

The World Health Organization defines workplace violence as “The deliberate use of physical force or power threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that has consequences or has a high probability of resulting in injury, death, mental distress, mal-development, or deprivation” (WHO, 2022).

Additional Resources:

- AI CBT apps and human counseling apps list, Finger Print of Success

- Empathy Test with scoring

- Preventing and Addressing Violence and Harassment in the World of Work through Occupational Safety and Health Measures. PDF.

- Verbal Judo©

- FBI active shooter training slide program

- Civilian Response to Active Shooter Events (CRASE) Train-the-Trainer is always available online for free at this website. Designed by the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training (ALERRT) at Texas State University.

- ADD Avoid Deny and Defend. Website.

- Free Self-defense courses for HCWs

- Free TeamSTEPPS 3.0 Curriculum Materials Webinar.

References

- American Nurses Association, (ANA). (n.d). Protect yourselves, protect your patients. American Nurses Association. Visit Source.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, (AHRQ). (2024). TeamSTEPPS 3.0 curriculum materials webinar. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Visit Source.

- Aljohani, B., Burkholder, J., Tran, Q. K., Chen, C., Beisenova, K., & Pourmand, A. (2021). Workplace violence in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health, 196, 186–197. Visit Source.

- Braun, B. I., Hafiz, H., Singh, S., & Khan, M. M. (2021). Health care worker violent deaths in the workplace: A summary of cases From the National Violent Death Reporting System. Workplace Health & Safety, 69(9), 435–441. Visit Source.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (BLS). (2020). Fact Sheet. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Visit Source.

- Cabilan, C. J., & Johnston, A. N. (2019). Review article: Identifying occupational violence patient risk factors and risk assessment tools in the emergency department: A scoping review. Emergency Medicine Australasia: EMA, 31(5), 730–740. Visit Source.

- Cabilan, C. J., McRae, J., Learmont, B., Taurima, K., Galbraith, S., Mason, D., Eley, R., Snoswell, C., & Johnston, A. N. B. (2022). Validity and reliability of the novel three-item occupational violence patient risk assessment tool. Journal of advanced nursing, 78(4), 1176–1185. Visit Source.

- Chand, S. P., & Marwaha, R. (2023). Anxiety. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Visit Source.

- Congress.gov. (2021). H.R.1195 — 117th Congress. Visit Source.

- Cyberbully. (n.d.) In The Free Dictionary by Farlex. Visit Source.

- De Sio, S., Cedrone, F., Buomprisco, G., Perri, R., Nieto, H. A., Mucci, N., & Greco, E. (2020). Bullying at work and work-related stress in healthcare workers: a cross sectional study. Annali di igiene : Medicina Preventiva e di Comunita, 32(2), 109–116. Visit Source.

- Dunsford J. (2022). Nursing violent patients: Vulnerability and the limits of the duty to provide care. Nursing Inquiry, 29(2), e12453. Visit Source.

- Edmonson, C., & Zelonka, C. (2019). Our own worst enemies: The nurse bullying epidemic. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 43(3), 274–279. Visit Source.

- ElHadidy, S., & El-Gilany, A. (2020). Violence among Pharmacists and their assistants in the community Pharmacies. Egyptian Journal of Occupational Medicine, 43(3), 727-744. Visit Source.

- Febres-Cordero, S., Shasanmi-Ellis, R. O., & Sherman, A. D. (2023). Labeled as “drug-seeking”: nurses use harm reduction philosophy to reflect on mending mutual distrust between healthcare workers and people who use drugs. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1277562. Visit Source.

- Gautier, C. (2019). Are you a bully? 6 signs according to a psychologist. Newsweek. Visit Source.

- Hvidhjelm, J., Berring, L. L., Whittington, R., Woods, P., Bak, J., & Almvik, R. (2023). Short-term risk assessment in the long term: A scoping review and meta-analysis of the Brøset Violence Checklist. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 30(4), 637–648. Visit Source.

- Ikeda, T., Hori, D., Sasaki, H., Komase, Y., Doki, S., Takahashi, T., ... & Sasahara, S. (2022). Prevalence, characteristics, and psychological outcomes of workplace cyberbullying during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: A cross-sectional online survey. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1087. Visit Source.

- International Labor Organization, (ILO). (2024). Preventing and addressing violence and harassment in the World of Work through occupational safety and health measures. International Labor Organization. Visit Source.

- Janzarik, G., Wollschläger, D., Wessa, M., & Lieb, K. (2022). A group intervention to promote resilience in nursing professionals: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 649. Visit Source.

- Jeong, Y., & Lee, K. (2020). The development and effectiveness of a clinical training violence prevention program for nursing students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4004. Visit Source.

- Jones, C.B., Sousane, Z., & Mossburg, S.E. (2023). Addressing workplace violence and creating a safer workplace. Patient Safety Network. Visit Source.

- Katella, K. (2022) How to be more resilient: 8 strategies for difficult times. Yale Medicine. Visit Source.

- Khalid, G. M., Idris, U. I., Jatau, A. I., Wada, Y. H., Adamu, Y., & Ungogo, M. A. (2020). Assessment of occupational violence towards pharmacists at practice settings in Nigeria. Pharmacy Practice, 18(4), 2080. Visit Source.

- La Regina, M., Mancini, A., Falli, F., Fineschi, V., Ramacciati, N., Frati, P., & Tartaglia, R. (2021). Aggressions on social networks: What are the implications for healthcare providers? An exploratory research. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 9(7), 811. Visit Source.

- Lim, M. C., Jeffree, M. S., Saupin, S. S., Giloi, N., & Lukman, K. A. (2022). Workplace violence in healthcare settings: The risk factors, implications and collaborative preventive measures. Annals of Medicine and Surgery (2012), 78, 103727. Visit Source.

- Liu, Y., Zhang, M., Li, R., Chen, N., Huang, Y., Lv, Y., & Wang, Y. (2020). Risk assessment of workplace violence towards health workers in a Chinese hospital: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 10(12), e042800. Visit Source.

- Lockertsen, Ø., Varvin, S., Færden, A., & Vatnar, S. K. B. (2021). Short-term risk assessments in an acute psychiatric inpatient setting: A re-examination of the Brøset Violence Checklist using repeated measurements - Differentiating violence characteristics and gender. Archives of psychiatric nursing, 35(1), 17–26. Visit Source.

- Luck, L., Jackson, D., & Usher, K. (2007). STAMP: components of observable behaviour that indicate potential for patient violence in emergency departments. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59(1), 11–19. Visit Source.

- Ma, Y., Wang, Y., Shi, Y., Shi, L., Wang, L., Li, Z., Li, G., Zhang, Y., Fan, L., & Ni, X. (2021). Mediating role of coping styles on anxiety in healthcare workers victim of violence: a cross-sectional survey in China hospitals. BMJ Open, 11(7), e048493. Visit Source.

- Mento, C., Silvestri, M. C., Bruno, A., Muscatello, M. R. A., Cedro, C., Pandolfo, G., & Zoccali, R. A. (2020). Workplace violence against healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 51,101381. Visit Source.

- National Institution for Occupational Safety and Health, (NIOSH). (2020). Types of workplace violence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Visit Source.

- Oguz, A., Mehta, N., & Palvia, P. (2023). Cyberbullying in the workplace: a novel framework of routine activities and organizational control. Internet Research, 33(6). Visit Source.

- Osibamowo, T. (2023). Dallas man who shot and killed 2 Methodist hospital workers gets life in prison for capital murder. Kera News. Visit Source.

- Pitts, E., & Schaller, D. J. (2023). Violent Patients. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Visit Source.

- Radomsky A. S. (2022). The fear of losing control. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry, 77, 101768. Visit Source.

- Senz, A., Ilarda, E., Klim, S., & Kelly, A. M. (2021). Development, implementation and evaluation of a process to recognise and reduce aggression and violence in an Australian emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia: EMA, 33(4), 665–671. Visit Source.

- Shulman, A. (2020). Mitigating workplace violence via de-escalation training. IAHSS Foundation. Visit Source.

- Strid, E. N., Wåhlin, C., Ros, A., & Kvarnström, S. (2021). Health care workers' experiences of workplace incidents that posed a risk of patient and worker injury: a critical incident technique analysis. BMC health services research, 21(1), 511. Visit Source.

- Texas State University Police Department. (n.d.). Emergency Procedures. Visit Source.

- Thompson, G. J., & Jenkins, J. B. (2013). Verbal judo: The gentle art of persuasion (updated edition). Visit Source.

- The Joint Commission. (TJC). (n.d.a). Workplace violence prevention compendium of resources. The Joint Commission. Visit Source.

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.b). Workplace violence prevention resources. The Joint Commission. Visit Source.

- World Health Organization, (WHO). (2022). Preventing violence against health workers. World Health Organization. Visit Source.